The 4+4 Days in Motion Festival in 2017 introduced the premieres of two productions with a noticeable “documentary” style approach, (which present true stories of existing people), even though they cannot be considered classic documentary theatre pieces. The given productions proceed from well-known situations, acted out as “true to life” as possible. In both cases the spectator becomes involved – either indirectly (as a participant of an apartment owners’ meeting) or directly (as an attendee of a training course). In this way the audience is not distanced from or superior to the absurdity of what is happening.

■ The atmosphere of the theatrical production called An Introduction to Computers – A Retraining Programme by Prague 9 Local Authority (originally a radio play by René Levínský) is anything but cosy. The spectators (attendees of the training course) enter an auditorium badly lit by fluorescent tubes, which hang very ungracefully from cables above their heads. The auditorium is furnished with tables on which a number of computers wait for the participants. We are consistently reminded that we are actually attending a real training course, and the illusion created is quite strong. The technical staff advise the spectators as they enter to take seats in pairs in front of the computer screens. From time to time we hear a slightly annoyed, monotonous voice, coming from the elevated stage. It repeats something that has evidently been said many times before: “Find a computer and just sit down.” The person who is speaking is completely hidden behind a huge computer screen, which the audience only sees the back of. However, we can watch everything that is happening on the instructor’s screen – on a large canvas hung on the left side of the stage. Before the training begins, the man gives some unpleasant yet resigned orders about the attendance list (“Pass it around, you can sign even for those that aren’t here, I know you are not here of your own free will…”), while surfing various e-shops, mainly selling computer equipment. He buys some antenna hubs, displays and batteries, but also spends considerable time choosing the right bath foam. His monologue has a refrain: “Just don’t bring it [i.e. the attendance list] here,” which is typical for the overall atmosphere of vagueness, the absence of normal human contact as well as the absurdity of the seemingly practical contents of the course.

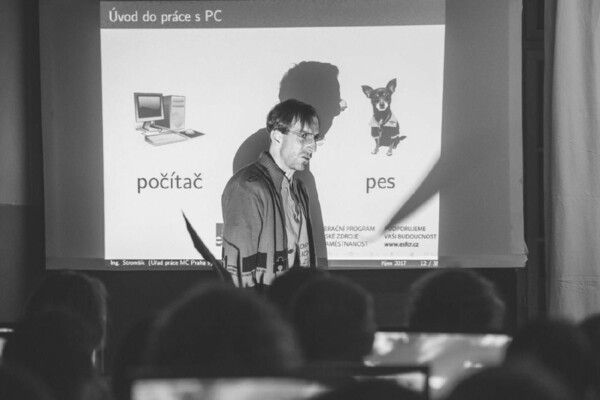

It takes quite some time before the up-to-now hidden lecturer, played by Petr Vaněk, leaves his hiding place and reluctantly launches “Introduction to the PC” the retraining programme for the unemployed. The slightly hunched man in glasses, orange polo-shirt and a worn-out brown sweatshirt introduces himself as MSc. Jaromír Stromšík from Prague 9 Local Authority. His contact with the participants remains very similar to when he was sitting behind his computer. He doesn’t look anybody in the eye, his eyes wander, and he is both slightly nervous and totally phlegmatic. He stammers when speaking, the result being quite unpleasant – he jerks his phrases and – what’s more – he speaks monotonously. One has to ask what would have to happen for this man to wake up.

Stromšík laughs at his own black humour and hopeless jokes (the jokes are not funny) without making a sound – thus what we get is something like a horrifying mute grimace. This is the type of anecdotal humour with which the instructor constantly seasons his lecture and which eventually makes up the greater part of the lesson. We get to hear his the very gloomy essential wisdom about life in phrases such as “never eat peanut butter near your keyboard, the damage is irreversible…something like death” or “you can hardly place a finger on the keyboard, if you don’t have one”. These musings and popular philosophy are interspersed with stories from Stromšík’s own tragicomic life. Levínský was inspired by a real person – that phenomenon of Czech internet debates, Michal Kolesa, who lived his life almost exclusively online. From time to time the instructor uses an exceptionally forced link to connect the content of his stories with one of the tasks for the participants. For example, when he needs to jump from a detour concerning the overratedness of taking showers nowadays, back to the topic of the course, he says: “(showering) won’t find you a job whereas a computer will”. The final outcome of such “unintentional” humour of this type and Vaněk’s interpretation of the lecturer as a consistently resigned man with autistic behaviour is very amusing – largely because Stromšík does not want to be funny at all.

The above-mentioned tasks for the participants form a sort of a refrain in themselves – from time to time Stromšík asks the attendees to answer the questions, which appear on their computer screens, either choosing from multiple choices answers or answering in their own words. It is only partially interactive – the lecturer never evaluates the results (he only congratulates his audience on completing the assignment); we never get to know the “right” answers. Which is not really a surprise. The questions are deliberately absurdly funny and in fact do not test anything, least of all any knowledge acquired during the course.

In between the assignments the lecturer most often goes into diverting litanies concerning his quite miserable personal life. Stromšík lives a similar life to that of his prototype, Kolesa – his only real human contact is with his mother. He is one of those guys who never leave their mother’s household. The relationship is clearly unhealthy – Stromšík for example mentions how he fancies walking around the house in his mother’s clothes. There are no other relationships in his life, his misogyny and fear of people leak from his every word and gesture. He loves computers exactly because they enable him to have as little human contact as possible. Fear in general is another recurring topic – during the course we learn the names of the most unbelievable phobias – logizomechanophobia, musophobia, metrophobia; one can fear just about anything and it seems that it is with this attitude that Stromšík approaches life and the world.

Fear comes hand-in-hand with scepticism in this production – the man is evidently doing something he does not believe in. Gradually he shows more and more contempt even for his employer – the Employment Bureau. According to Stromšík people do not need more skills and he is not willing to make an effort to teach them. His resigned attitude culminates when he is supposed to connect the computer to a 3D printer. However, by mistake he does quite the opposite, flattening 3D reality…and thus even himself. He disappears from the stage and from then on we only hear his voice from the loudspeakers of the computers. An idyllic beach appears on the computer screens and it seems that Stromšík has just achieved absolute happiness: “It is beautiful here, as if the sun was rising.” The humming and buzzing of the machines mingles with the sounds of the waves, crashing on a shore. However, it only takes one click and the idyll will be over, so you should “NEVER SWITCH OFF THIS COMPUTER!!!”

After the first few performances the creators supposedly perfected the whole concept in that Petr Vaněk did not even come back for the curtain call. It seems to me that after the final “sci-fi” part, which comes rather unannounced (Stromšík’s diverging blabbering does not lead anywhere anyway, it could be interrupted at any time), such a solution, (the actor not making a return even for the curtain call) makes sense and it would be worth it to get back to it – because it didn’t happen in the performance I saw.

However, in my view Stromšík’s disappearance from the stage, and the long final scene, in which the audience has to make do with a reproduced voice, disrupt the tempo and energy of the previous events. Vaněk has managed not to caricature Stromšík, he plays him with a certain empathy and respect. Without the live person on stage there is suddenly no tension between the pitiful and pathetic course and its lecturer and the sympathy the audience can feel for someone, who defies the definition of “normal”.

■ The independent theatrical group Vosto5 performs The Association of Unit Owners in the public auditorium of the Masaryk Railway Station, an ideally impersonal and un-theatrical space: a run-down space of unclear purpose, lit by fluorescent tubes. The director Jiří Havelka and the Vosto5 group have a habit of unobtrusively making the spectators part of the event, of erasing the boundaries between the audience and the actors. This is usually clear straight away from the initial organization of the space. Just as in the production called Brass Band (Dechovka, 2013), in which the audience became guests at a pub, in The Association of Unit Owners they become the participants of a regular meeting of house owners. They are seated in two rows around a long table, just a step or two from the debating protagonists.

From the beginning we are led to believe things are “for real”, as if watching a documentary. The last spectators are not yet seated, when the first participants of the meeting start to come in. They choose their seats by the table, which is decorated with artificial flowers (there are also drinking glasses for everyone as well as a copy of the civil code). The first moments show how important it is to create just the right mix for this neighbourly “stew”. First and foremost they maintain the “documentary” feel (well-known actors would not do as well here) but also they show the widest possible range of human types, characters, personal defects and frustrations, which don’t take long to come out in this micro-war for power and for stating one’s own importance. This goal is fulfilled perfectly – and if you have ever attended such a meeting with the aim of solving a shared problem, you will surely “recognize” most of the characters here.

The association is chaired by a young mother currently on maternity leave (Renata Prokopová[1]/). She tries to be constructive and keep the debate polite, however even she eventually breaks down and hysterically vents her anger and despair on her husband. He is played by Ondřej Bauer; as an inconspicuous consensual type; who wants to help his wife and avoid unnecessary arguments. Nevertheless even he gets more than angry when confronted with his wife’s accusatory fit and we learn a lot about the way their relationship works (or rather doesn’t work). Their micro-story is sort of typical of the whole production – in the end it’s more about washing dirty linen in public than about finding a solution to common problems.

Solving problems would be kind of hard, given such “material”. Mrs Horváthová (Hana Müllerová), a pensioner in a tasteless pink dress, is mostly interested in the possible advantages others might have over her when paying the rent or energy bills and in how such injustices can be prevented. She is a typically envious concierge, with eyes everywhere. She is especially wary of the young Slovak homosexual Nitranský (a double target for the older generation), who should be paying – apart from other things – much more on water consumption as his lovers who keep strolling around the house smelling good must use up an enormous amount of water. Nitranský (played by Andrej Polák) tries to be rational but he is hot-tempered, as Slovaks can be, and not much of a diplomat. Moreover, he enriches the debate with such notions as solidarity, civilization and European values, which does not him popular with the “old school” residents and soon all sides attack him. He is the first to leave the ever-tenser atmosphere, (full of the unscrupulous attacks of the various unrelenting opponents). He leaves for good when accused of putting sap-rot in the attic, so that he could buy the place for himself.

Conspiracy theories and suspicion flowers in a situation concerning common property. The pensioner Kubát (Ján Sedal), former chair of the association and the guardian of the old (that is “communist”) order, is a master of this art. For him, the good times had already passed. He is exceptionally cunning, intolerant and stubborn. Miloš – as the other owners call him – has an argument against everything that is “new”. Gradually we learn that he was married to Horváthová, whom he constantly offends, and that they have an adult son of doubtful morals. Kubát owns several apartments in the house, which he obtained in an evidently illegal manner. His answers to everything are “forget it” or “NO is the reason”, which blocks all further debate.

One of his apartments is inhabited by a professor (Václav Poul), who pulls a book out of a plastic bag right in the beginning and reads throughout the whole meeting – apart from a single intervention, in which he recommends not getting rid of the gas distribution in the house. Given the increasing senselessness of the meeting one cannot entirely blame him for his indifference; however his attitude mirrors the arrogance of the intellectual elite and their detachment from everyday life. Regardless of all the humour, the production clearly makes the unwillingness to overcome boundaries between social and other groups one of its themes – and not only in the character of the professor.

A young husband and wife, new in the house and thus as easily manipulated as they are lost in the relationships and issues, also do not contribute much to the debate. The wife (Anna Kotlíková) is heavily pregnant and keeps silent. She is clearly in pain and has to leave for the toilet followed by her startled husband (Patrik Holubář). By contrast, the evidently rich Mrs Procházková (Lenka Loubalová), a chic blonde in a pink two-piece suit, is amused and unconcerned; she puts on make-up during the debate and mocks the others with open contempt. She has a sort of silent coalition with her suspicious escort-adviser (Zdeněk Pecha), who turns out to be a rather primitive thresher and the owner of a small company that can arrange anything and everything. He quite untrustworthily offers his services whenever he can.

We should not forget the extraordinarily blockheaded Mr. Švec (David Dvořák) who keeps swigging from a bottle and gets drunk while eating up all the food served for everybody. More importantly, he doesn’t have a clue about anything that is being debated. He speaks off topic all the time (especially about his ill mother, whom he is standing in for) and raises his hand both in favour of a solution and against it. Another notable figure, Mrs Roubíčková (played by Halka Třešňáková), is an unbearably stiff hair-splitter, who takes her role as auditor very seriously. She keeps pulling at her tiger-like neckerchief with an unpleasant and unapproachable expression. She wants every nonsensical detail to be put on paper and offers bulletproof phrases such as “statutes are statutes” – and quoting from official documents seems to be her hobby.

And last but not least, we should introduce the slightly mysterious twins, the Čermák brothers (Petr Prokop and Ondřej Cihlář). They have just returned home after a long period of doing business abroad, and have inherited their father’s apartment in the house. They are trying to understand the situation, apart from which they discover that almost every neighbour has keys to their father’s apartment. At first the brothers make an impression as business-like professionals, not wanting to interfere. Gradually they start to offer the services of their company, finally getting a grip on the situation. All those who are able to spend half an hour debating on who shall be the registrar and who the auditor, what the correct voting procedure is and other such marginalia; all those who are not able to agree on any mutually acceptable compromise regarding the main topic of the meeting – the sale of the attic and the reconstruction of the house – suddenly without hesitation sign blank papers, “just little powers of attorney”, as the brothers call them. Better not to know what these people actually signed and what they will find out in the next meeting, which will be chaired by the Čermák brothers (and the totally drunk Švec), who quickly had themselves elected in the chaos after the hysterical breakdown of Mrs Zahrádková.

The total chaos is rooted in the absence of a will to find a solution, in the inability to really listen to others or engage in meaningful discussion. Some of the characters have a special tendency to concentrate on that which is of no consequence. The debate goes round in circles, people shout each other down and talk nonsense – nevertheless, under all this banality we can clearly sense some important social issues. Racism is the first that comes to mind – the six students from Ghana that live in the apartment rented to them by Mrs Procházková are a topic for everyone. Except for the two younger married couples, people show a similar intolerance when confronted with homosexuality. As one of the offended characters remarks: “Today gays have more rights than people.” It is symptomatic that at the beginning everyone is quite careful, making nonspecific remarks, but when one gets somebody else’s support, he or she attacks with not a whit of political correctness.

Even the strictly “documentary” form of a classic house meeting of this kind does not survive the surge of all these emotions. Havelka disrupts it with a good sense of timing. When the situation gets critical, we can clearly feel the mutual hatred – and it seems that the negotiations are at a dead end – the pregnant wife starts to give birth. A “slow-motion” sequence follows, which hyperbolizes the drama into operatic proportions, supported by a musical accompaniment. The room is half-covered in a misty haze through which all the protagonists make their way in an attempt to help the woman in labour (or they at least pretend to). They open their mouths in pure horror and perform absurd life-saving gestures, plunging across the table to grab a cell-phone or towards the window to open it… The result is part comedy, part freak-show – a Bosch painting come alive. When the woman in labour calls out “false alarm”, the scene ends as abruptly as it began, the atmosphere and tempo go back to normal, as if nothing had happened. Mrs Zahrádková and Roubíčková perform another such unexpected comical sketch (in which they expose themselves as quite ridiculous and pathetic). At the moment the hysteria reaches its peak and people’s dirty linen of the most personal kind is coming out, the two women start running around the table and fighting each other with their bare hands. The rest of the neighbours watch the scene with no sign of interest. Only Kubát makes a wry comment in the end: “Oh please, Hanka, just let her go.”

The ending has an atmosphere of almost horror. Some of the neighbours have already left the room, the rest are packing their stuff. The Čermák brothers take advantage of the chaos for a “coup d’état”. The fact that no one is able to see through their trick makes one worry about human stupidity. The lights are half turned out and we hear a gloomy roaring, which could be a sign that something may really be wrong with the gas distribution in the house. The overall disintegration is symbolically rounded off with the sudden loosening of one of the overhead lights…However, the real horror consists in the fact that after an hour and a half there is absolutely nothing written down in the minutes of the meeting – a document where the residents wanted to have “only the things that matter”.

René Levínský: An Introduction to Computers – Retraining Programme of Prague 9 Local Authority, directed by Johana Švarcová, dramaturgy Marta Ljubková, music Martin Ožvold, stage design and costumes Adriana Černá, premiere October 8, 2017 as part of the 4+4 Days in Motion Festival

Jiří Havelka: The Association of Unit Owners, directed by Jiří Havelka, dramaturgy Martina Sľuková, stage design Antonín Šilar, costumes Andrea Králová, Vosto5, premiere October 7, 2017 as part of the 4+4 Days in Motion Festival

published in Svět a divadlo, issue 3, volume 2018

translated by Ester Žantovská

[1]) I am mentioning the actors that I saw. Some of whom were understudies.

Learn

Learn