Czech theatre production can be roughly divided into three groups: well-established “brick-and-mortar” theatres, private commercial theatres that were founded after the end of the Communist regime and an unclear wide spectrum of more or less independent alternative groups, and production groups, which fill up the space between the two poles. Apart from these institutions, there are several puppet theatres with long tradition and their own buildings (they play for children but not exclusively) and the important part of the system is a strong and well-organized amateur theatre movement.

Apart from three “national theatres”, there are theatres directly funded by the state (town or regional budgets) and ensembles who receive money for their operation from various grants. However, the system has not settled down yet, which results into disputes and conflicts as well as problems emerging from the effort of political representation to influence the form of theatres funded by the state or towns. One of the traditional centers of out-of-Prague theatres has almost ended its activities: it is Činoherní studio Ústí nad Labem (it has the new name of Činoherák Ústí na Labem since 2014). One year later, the town representatives willfully terminated a thoughtful attempt of the art director of the Municipal Theatre in Kladno to upgrade the local stage to dramaturgically ambitious production with a concept, which is not very common speaking of regional theatres (Kladno is a satellite town with 70,000 inhabitants). The positive thing is that the system of multi-year grants has been implemented and allows middle-sized theatres and ensembles to work continually. It is worth mentioning that the Czech Republic has a very dense network of theatres with permanent ensembles (nine opera houses included) and bigger towns see the existence of their own theatre as prestigious.

There have been several essential changes in the management of important Czech drama theatres. The most closely observed change was the new art director of the National Theatre drama (this is a position that draws most attention in Czech theatre). Daniel Špinar (born 1979) took over the position in 2015 and confirmed the onset of the strong generation of the people in their thirties to fundamental positions in Czech theatre, which has been supported by the arrival of his classmate Jan Frič (1983), who is another key director in the National Theatre. The director of the National Theatre Brno Martin Františák (1974) is the member of this generation as well as the new creative team of the Theatre on the Balustrade in Prague (the former “Havel Theatre”) with dramaturge and art director Dora Viceníková (1976), director Jan Mikulášek (1979) and stage designer Marek Cpin (1979): all of them started in autumn 2013.

Important changes happened in opera companies in national theatres. Silvia Hroncová (1964) has been the director of opera in the National Theatre and State Opera in Prague since the season 2013/2014 with the art director being the composer, conductor and promoter of the non-traditional attitude to opera Petr Kofroň (1955). Progressive director Jiří Heřman (1975) was appointed the art director of the Janáček Opera in Brno and Marko Ivanović (1976), the composer and modern opera promoter, is now the chief conductor famous for his willingness to cooperate with alternative theatremakers outside the field of music theatre. Since modern opera is welcomed in the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre in Ostrava (the director of the theatre is Jiří Nekvasil, the opera director with modern attitudes), all three theatres carry through a progressive form of music theatre placing more demands on the audience – in contrast with much more conservative production in small regional opera houses.

Speaking of the geographical point of view, the situation in Czech theatre is relatively stable. Except for Prague and Brno, the theatre in Ostrava offers the liveliest theatre stage: all three cities have National Theatres with more ensembles as well as smaller chamber or alternative stages, and theatres for children. Several strong companies in regional towns surpass the regional level: Hradec Králové (Klicpera Theatre) or Plzeň (J. K. Tyl Theatre). These are also towns hosting the two biggest Czech international theatre festivals (Theatre of European Regions and Theatre Plzeň). Theatre has a traditionally strong position in České Budějovice (South Bohemian Theatre), Liberec (F. X. Šalda Theatre and puppet Naïve Theatre) or Uherské Hradiště (Slovácké Theatre). All the theatres regularly invite top guest directors from Prague or Brno, which is yet another way to stage productions out of routine operation.

Nevertheless, the independent theatre groups are those creating the liveliest segment of Czech theatre recently; they can be fully professional with their own venue (it is sometimes shared, though – like in VILA Štvanice) or small and not fully professional groups with changeable members. The typical centers are production houses, in which a group of theatremakers and companies with similar visions are concentrated, such as Alfred ve dvoře in Prague (the alternative and experimental theatre center), Alta Studio and Ponec (specializing in motion theatre), or Jatka78 focusing on contemporary circus. Prague dominates this field and is followed by Brno, although there is a big gap. Such activities are not as frequent as in the two cities as there is also a lack of spaces where the alternative companies can stage their productions: Moving Station in Plzeň, DIOD Jihlava, D21 Pardubice.

Czech theatre still maintains a strong tradition of interpretation drama even though young and middle-aged theatremakers gradually digress from this trend (as they are influenced by the Prague German Language Theatre Festival, the showcase of the top German-speaking theaters). However, all big and regional theaters respect the pressure of the conservative audience and they do not explore the area outside the time-proven drama much. The same applies to staging Czech playwrights. With the new art directors, National Theatres in Prague ad Brno are exceptional in this matter as they are willfully trying to get rid of the deep-rooted conservative attitude many viewers have, although they have not chosen a revolutionary way. Brno has seen many audience-friendly productions as well as provocative attempts of guest directors: classic adaptations such as Demons (adapted by Roman Sikora and directed by Martin Čičvák), Fassbinder’s Fear Eats the Soul (directed by Jan Frič) or the attempts in author’s production, which maps the state of contemporary society (Kmeny/Tribes directed by Braňo Holiček). Daniel Špinar, the new artistic director of the National Theatre, has significantly rejuvenated the ensemble and has introduced several new dramaturges, with whom he cooperates to enforce his vision of elegant visual theatre inspired by Robert Wilson (Othello or Manon Lescaut). The experimental and less audience-friendly productions are in the repertoire of New Stage, the only more contemporary (yet not chamber) space the National Theatre has now. Even René Levínský, the playwright and mathematician, who wrote the plays for his amateur company and worked his way up to the most unusual contemporary author, had his premiere here (Press Space to Continue) directed by Jan Frič.

The traditionally strong segment of Czech theatre is small “club” stages, which are favored by both audiences and reviewers. Dejvické Theatre or Theatre on the Balustrade, Chamber Venue Aréna in Ostrava or HaDivadlo in Brno have recently received most of the awards in the prestigious survey of Czech theatre reviewers. Theatre on the Balustrade is a record holder in 2013 as it received the first prizes in all eight categories, mainly due to Jan Frič’s production Velvet Havel. However, it was mostly persisting fascination by the recently deceased playwright and president, which had its share in the outstanding reception of the cabaret reviewing the life of Václav Havel with amiable irony (Miloš Orson Štědroň composed music and libretto). Chamber Venue Aréna in Ostrava was elected the theatre of the year and it combines acting theatre with semi-documentary production of local dramaturge Tomáš Vůjtek. In 2015, the award went to the production of Hearing (about Adolf Eichmann) and the production With or Without Hope about the wife of a Communist apparatchik beheaded in the trumped-up Stalinist trial in the 1950s received the prize in 2013.

It is rather symptomatic that the piece with the character of Václav Havel received the prize in 2016 as well: the Letí Theatre from Prague succeeded with their production of Anna Saavedra’s Olga/Hrádeček Horrors, whose protagonist is Havel’s first wife. The two awards (for the best play and the best performance) give evidence that companies from the above-mentioned fields of small, alternative and non-regular theatres hold very strong positions in reviewers’ survey. Except for the Letí Theatre with their venue of the reconstructed dancing hall on one of the islands in Prague (with two other companies), the team of Lukáš Brychta, the most significant Czech promoter of immersive theatre, was awarded as well. The same category of the “theatres on the edge” also contains ensembles in Alfred ve dvoře, the miniature but prestigious theatre house focused on theatre alternative. One of the stable companies is Handa Gote Research & Development with their slightly surreal visual style (Mutus Liber or Erben: Dreams), director Jiří Adámek’s Boca Loca Lab specializing in original rhytmic recitation is successful as well (they attracted the viewers’ attention in 2016 with their “spoken opera” The Infinity of Lists). NoD experimental space focuses on new writing and Venuše ve Švehlovce, the former rock club with several semi-professional companies dealing with performance, political and documentary, is on its rise as well.

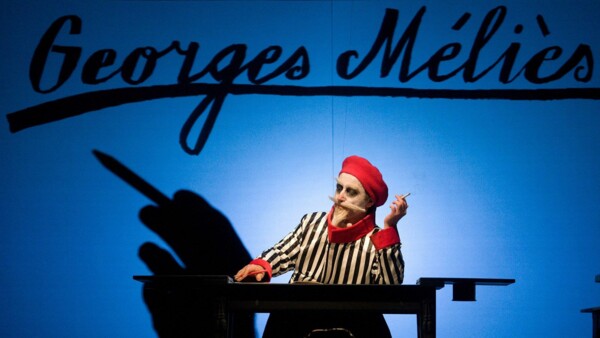

Apart from the production for children, many Czech puppet theatres come with ambitious projects for adult viewers as they see it as a matter of honor. The results of the Czech theatre reviewers’ survey prove that the productions for children rank among the most successful ones. In 2015, Marek Doubrava received the award for best music in Adámek’s production Libozvuky (which was visually special as well) in Minor Theatre. In 2014, the third prize for the best production went to the visually precise poetic production O beránkovi, který spadl z nebe for the kindergarten children staged by Naïve Theatre in Liberec and directed by Michaela Homolová. Generally speaking, puppet theatre has been losing its popularity: traditional marionettes cannot be seen so often, puppets started to share the stage with live actors or serve as an addition to visual productions. One of the typical examples may be the successful production of Georges Méliès’s Last Trick directed by Jiří Havelka in the DRAK Theatre in Hradec Králové.

Czech opera has experienced good time despite the fact that it cannot afford costly productions with world-famous singers (yet they played in Miroslav Srnka’s premiere of South Pole opera in Munich). Unlike drama, Czech opera houses cooperate with first-rate foreign conductors and directors (opera productions of drama authors are frequent as well) with significant young and middle-aged Czech directors and composers. Jiří Heřman succeeded in the National Theatre with his production of the nearly forgotten romantic opera The Fall of Arkun by Zdeněk Fibich (conducted by John Fiore) but we have also seen interesting attempts working with topics classical opera usually avoids, such as Aleš Březina’s Toufar reminding us of the life of the catholic priest, who was tortured to death by the Communist secret police in the 1950s (Březina’s previous opera Tomorrow There Will Be… about the judicial murder of politician Milada Horáková was successful as well). The National Moravian-Silesian Theatre in Ostrava continues in the NODO biennial (New Opera Days) with the presentation of new pieces by Czech and foreign composers. The symbolic acknowledgement of the contemporary position of opera is a recent success of the National Theatre in Brno with the performance Bluebeard’s Castle/Expectation (directed by David Radok and conducted by Marko Ivanović); it received the award for the best production in 2016.

National Theatre Ballet, the most respected Czech ballet company, has been managed by dancer and choreographer Petr Zuska (1968) since 2002; his most significant production is Tremble (2017), the original feature production with the topic of migration. The biggest success of the company was the production Decadance (2015) by Israeli dance Ohad Naharin – it is the variation to choreography he danced with his Batsheva Dance Company before. His guest performance was also the first encounter with the gaga method Naharin uses to engage the personality of every performer to shape the final version of the production.

The small and independent companies with international cast are those with most activities in dance and motion theatre. The perennial stars are DOT 504 with the creative duo Jozef Fruček and Linda Kapetanea developing dark poetics related to Wim Vandekeybus, or rather academic company 420PEOPLE founded by Nataša Novotná and Václav Kuneš, the former members of the Kylián’s Nederlands Dans Theater. One of the certified and internationally acknowledged brands is Farm in the Cave managed by Viliam Dočolomanský, which focuses on the “sociological” attitude in production: the company researches a phenomenon for a certain period of time and then creates a production. In 2015, Farm in the Cave started to play Disconnected about the hikikomori, the voluntary renunciation of all social relations. The most successful motion production in this category was Gossip by Lenka Vagnerová & Company, which premiered in La Fabrika in 2015 and deals with gossip and its impact on the people. Spitfire Company can boast with good international response and many successful guest performances all around the world; it combines alternative drama and motion theatre. The piece with the biggest reception was an original adaptation of Václav Havel’s one-act play Audience, which was renamed to Antiwords (2013); the conversation between Havel’s alter-ego Vaněk and caricatured representative of the corrupted society played by two actresses turns into a grotesque performed in horrific masks covering the heads.

Popularity of contemporary circus has been growing recently in the Czech Republic due to the festival Letní Letná, which brings world-famous stars to Prague every year as well as the success of Czech companies. La Putyka managed by Rosťa Novák ranks among the most popular ones. The new space Jatka78 in the former slaughterhouse (now a market) was a great breakthrough as there are also other companies and regular guest performances of foreign contemporary circuses.

categories

Seasons’ overview

Author

Vladimír Mikulka

Learn

Learn